I’m Luke Craven; this is another of my weekly explorations of how systems thinking and complexity can be used to drive real, transformative change in the public sector and beyond. The first issue explains what the newsletter is about; you can see all the issues here.

Hello, dear reader,

tl;dr: Systems thinking and complexity theory can be understood as a form of spiritual practice. They help us explain what the world is, how it works, and what that means for how we should live.These days, I don’t listen to many podcasts. It’s hard to find one that consistently draws me in, but On Being is a notable exception. Understated and magnificent, On Being is a series of conversations that take up the great questions of meaning in 21st-century lives and at the intersection of spiritual inquiry, science, social healing, and the arts. Host Krista Tippet typically begins each of her interviews by asking her guest about the spiritual background of their childhood. A small but revealing question, Tippet’s view is that the spiritual threads of our lives shape how we each begin to answer the animating questions at the centre of human life: What does it mean to be human, and how do we want to live? I really can’t recommend it any more highly.

My own story is one of contradiction. I grew up in a secular household, but religion found ways to be a defining feature of childhood. My father, who is probably the staunchest rationalist I know, came from a family that was deeply involved in the Salvation Army. I have the strongest memory of his mother, toward the end of her life, entrusting thirteen-year-old me with the task of policing which bible translations could be used at her funeral (“King James Version only, please. None of that other rubbish”). I wound up at a Christian high school where religious education was included across all elements of the curriculum. I was an ardent teenage atheist, but I’m bad at tuning out. I took it all in. I can see how it is easy to get caught up in the dogma and doctrine, but that is not what I took from the experience. Being sceptical about, but surrounded by, religion is a lesson in how it is just like any other sense making practice. It is an attempt to understand parts of our existence that we can’t possibly understand. It creates a language and a set of practices to live with and be comfortable in that not-knowing. It is a recognition that we are all stuck somewhere between rationalism and faith, which is an intensely uncomfortable place to be.

Systems thinking and complexity are often spoken about as a way to make sense of the “real world” and our experience of it at a high level of fidelity. They are often couched as a response to ways of understanding the world that see it in Linear, Anthropocentric, Ordered and Mechanistic (“LAMO”) ways. The argument is that by taking a systems or complexity view we are able to see that:

Everything is connected—the world is a Complex Adaptive System.

We are part of that system and our choices can contribute to positive dynamics or feed dysfunctional ones.

We can cultivate strengths within ourselves that enable us to make wiser choices.

As complexity theory gains popularity, I increasingly hear people say things like “the world is complex so complexity theory must be the answer” and “we can understand it properly but first we have to accept that it is complex.” Statements like these are well meaning but are often phrased in worryingly dogmatic terms. As I’ve previously written, the acknowledgement that something is complex implies that our knowledge of it will always be limited. Using complexity theory to make decisions about how we ought to act always involves big leaps of faith. Some of those leaps might be justified by the principles of complexity and others are probably informed by aspects of human intuition we struggle to explain, but they remain leaps of faith. A complex view is always partial and provisional. Attempts to hype up complexity theory as way to gain a more objective, unifying view of the world would do well to heed Plato’s warning:

“Whenever I deem another man [sic] able to discern an objective unity and plurality, I follow in his footsteps where he leads as a god. Furthermore—whether I am right or wrong in doing so, God alone knows.”

To be clear, I am not suggesting that we should abandon complexity theory or that it is not a useful tool for making sense of the world around us. It explains some of my experience of a messy world and perhaps it explains some of yours too. This is what all spiritual practices attempt to do—explain unity and plurality amidst complexity; collapse the distinction between faith and reason. Stuart Kauffman, a complex systems researcher who studied the origins of life on earth, has said that much of what we have sought from a supernatural God is the natural behaviour of the emergent creativity in the universe. This seems to me not so different to what we seek from the secular promise of complexity theory. We want to know how the world works.

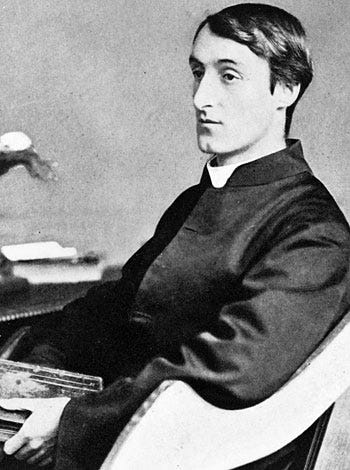

One thing I did take from my religious schooling was a love for the Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. A Jesuit priest, much of Hopkins’ work had religious themes and was his attempt to capture and explore his awe and reverence toward nature and creation.

A favourite poem of mine is Pied Beauty, in which Hopkins positions God as the explanation for the multiplicity of the natural world. The poem was written in 1877, around the same time Darwin’s theory of natural selection was gaining traction beyond the scientific community, but was not published until 1918, when it was included as part of the collection Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Glory be to God for dappled things —

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches' wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced — fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

Hopkins’ view is that the variation, difference, and emergent creativity in the world can be explained by God’s power and inspires us to “Praise him”. Hopkins implores the reader to see great variety in the natural world not as a result of evolution (notice the subtle allusion to Darwin’s finches), but as a testimony to the perfect unity of God and the unlimited nature of his creative power. But ultimately, as Hopkins himself suggests, who really knows how this multiplicity is created or sustained? Whether his perspective is right or wrong, God alone knows. For a devoutly religious man, this is an extraordinary claim of modesty. Despite everything, he too is stuck somewhere between rationalism and faith.

A disclaimer…

It is worth noting that religious and spiritual practices are not necessarily systemic or, at least, not systemic in the same way. Many Judeo-Christian belief systems strongly emphasise humanity’s dominion over nature, for example. Even if they help believers make sense of nonlinearity and complexity in the world around them, they do so through an inescapably anthropocentric lens. One of the reasons for Christianity’s anthropocentrism can be found in Genesis 1:26-28 (King James Version, of course). There we see that God made humans in his own image and that he gave them “dominion” over every living thing upon the earth. Throughout history, many Christians, even up to the present day, have read this to mean that human beings are the most (or even only) valuable part of Creation. Many non-Western and Indigenous spiritual traditions start in a completely different place; by emphasising the entanglement of human and non-human and engaging with that complexity through a relational-lens. Given my own Judeo-Christian upbringings, I can’t help but reflect on how that has left me poorly prepared to engage with eco-centric and relational ways of seeing the world.

By the way: This newsletter is hard to categorise and probably not for everyone—but if you know unconventional thinkers who might enjoy it, please share it with them.

Find me elsewhere on the web at www.lukecraven.com, on Twitter @LukeCraven, on LinkedIn here, or by email at <luke.k.craven@gmail.com>.