#18: T. S. Eliot and the Middle Way

A quiet reflection on The Waste Land, emptiness, and the Buddhist philosophy of the Middle Way.

I’m Luke Craven; this is another of my weekly explorations of how systems thinking and complexity can be used to drive real, transformative change in the public sector and beyond. The first issue explains what the newsletter is about; you can see all the issues here.

Hello, dear reader,

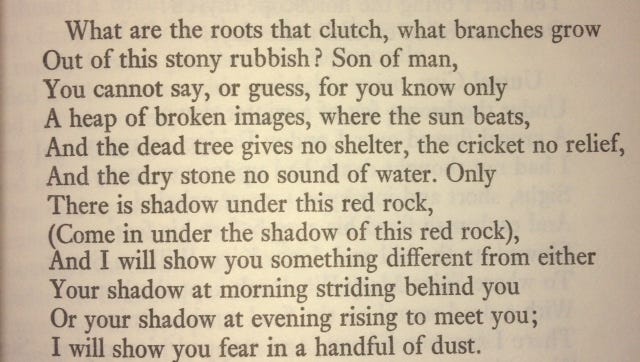

This issue wont be for everyone, but I hope it will resonate with some. It is a quiet reflection on T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, and the Buddhist philosophy of the Middle Way.Many of you would have read—or been forced to read—T. S. Eliot’s masterful poem The Waste Land, widely regarded as one of the most important poems of the 20th century and a central work of modernist poetry. I’ve been fascinated by this poem for a long time, For a good chunk of my teenage years, I could recite three of the five parts by heart (yes, I’ve always been this fun…!).

More recently, I have started to read The Waste Land as an allegory for our experience of complexity. To read The Waste Land is to be overwhelmed by half-formed meanings. Eliot throws these half-meanings into our field of vision with such intensity that no thread of coherence can reach completion. As Ruth Nevo puts it, the poem:

Has no narrative, time, or place; no protagonist; no drama, no epic, no lyric; no one point of view, no single style, idiom, register; no identifiable overall subject matter, or argument, or myth, or theme; no obvious conventional poetic features such as meter, rhyme, stanza, or any regularity or recurrence or set of symmetries which would constitute formal pattern in any classical sense at all.

Its symbols refuse to symbolise … [they] explode and proliferate … [they] turn themselves inside out, diffuse their meanings, and collapse back again into disarticulated images. (455-6)

To make sense of complexity is to carve out islands of meaning from these half-meanings—to create “certainty artefacts” that can anchor us to moments of coherence, however fleeting. Experience is an attempt to impose order where none exists.

Eliot was fascinated by the connection between experience and reality. In his little-known PhD thesis, Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley, he grapples with the idea of truth and the limits of perception.

Building on the work of F. H. Bradley, Eliot argues for a pragmatic theory of knowledge in which everyday experience (“immediate reality”) is set against the prospect of objective truth (“the Absolute”). He notes that:

There is a real world, if you like, which is full of contradictions [immediate reality], and it is our attempt to organise this world which gives belief in a completely organised world [the Absolute], a hypothesis which we proceed to treat as an actuality. (p.90)

On this reading of Bradley, the Absolute should be seen as a useful hypothesis. It is the prospect of an ordered reality, for which we all strive. We regard it as actually existing, even if only in prospect. This belief gives purpose and meaning to human existence, but the Absolute is impossible to practically realise, if it exists at all. It is only meaningful insofar as it helps us give shape to our experience of disorder and complexity.

It is well-known that Eliot engaged deeply with Buddhist philosophy, most notably the Mādhyamika or Middle Way Buddhist philosophy of Nāgārjuna. The central thesis of Nāgārjuna’s work is that that nothing exists in itself, independent from something else. Everything exists in relation. The technical term to describe the absence of independent existence is emptiness (śūnyatā): things are ‘empty’ in the sense of having no autonomous existence.

Much like Bradley, Nāgārjuna’s writing distinguishes between two types of truth: conventional truth and ultimately reality. Like Bradley, he argues that ultimate reality does not exist except in relation to our experience of conventional truth. It too is empty: a perspective that does have autonomous content or form. It is easy to read this position as nihilism, but Nāgārjuna saw it as liberating. Without a foundation in conventional truth—our everyday experience and understanding—the significance of the ultimate reality cannot be taught. Without understanding the significance of the ultimate reality, liberation cannot be achieved.

I readily accept this is complicated philosophy. I read each of these texts in a particular way and I don’t claim that my reading is in any way conventional. But that’s the point, isn’t it? Reading The Waste Land, like living in this world, requires a plurality of consciousness. Each is an ever-increasing series of points of view, from which we struggle to create an emergent unity. Perhaps we should take solace in the realisation that there is none to be found. As Eliot himself writes, maybe the best we can hope for is a heap of broken images.

By the way: This newsletter is hard to categorise and probably not for everyone—but if you know unconventional thinkers who might enjoy it, please share it with them.

Find me elsewhere on the web at www.lukecraven.com, on Twitter @LukeCraven, on LinkedIn here, or by email at <luke.k.craven@gmail.com>.

I've also had a long-term interest in The Waste Land, from when I was a Humanities academic teaching on the history of ideas and their expression in culture - though with more focus on the other great spiritual tradition that shaped Eliot, Christianity. There are some very similar resonances from that tradition to those you call out, albeit from a very different ontology: The belief in the incarnation of Christ, absolute truth being embodied in grounded everyday reality for instance, in a way that totally disrupted Greek Platonist thought about the strict separation between the ideal realm of forms and the imperfect shadow physical reality; the inherent relationality in the concept of the Trinity; the rejection of autonomous being apart from God; and a concept that you didn't call out, a highly relational epistemology based on love as an essential prerequisite for truth. As broken as the images are, their truthfulness is only fully experienced when the perception is grounded in love ...

I've been reading a lot about Modernist literature recently, so this felt uncannily timely!