I’m Luke Craven; this is another of my weekly explorations of how systems thinking and complexity can be used to drive real, transformative change in the public sector and beyond. The first issue explains what the newsletter is about; you can see all the issues here.

Hello, dear reader,

Boy, the weeks fly by! Increasingly, I’m only managing to get my posts half cooked by my self-imposed Tuesday afternoon deadline. So, this week’s newsletter should be read as a series of fragments that are still rolling around my brain in search of a narrative to hold them together. Hopefully you’ll permit me an indulgence, just the once 🙏🙏

It’s more complicated than calling it complicated

I have received a lot of feedback on the earlier issue of this newsletter that argued that all systems are complex systems. Feedback has broadly centred on whether simple or complicated problems can exist inside complex systems. We all, in our attempts to make sense of complexity, draw boundaries around particular problems or areas of exploration to make them meaningful and actionable. But, we should always treat those boundaries with a healthy scepticism. The overemphasis on closure that comes with calling something simple or complicated always leads to an understanding of the problem that underplays the role of the environment. In practice, this plays out in a number of ways:

All policy decisions involve making trade-offs between competing claims for a finite pool of resources. No decision exists in a vacuum. Choosing to scope and explore a particular problem area means prioritising it over other, equally-deserving issues. When budgets and political will are both scarce resources, prioritising solutions in a problem space will always involve making decisions that leave some stakeholders worse off, on at least some of the metrics that matter to them. People often talk about building a bridge or sending a rocket to the moon as examples of problems that are complicated. Both of these examples are exceptionally resource intensive and necessarily prioritise particular policy objectives above others. At one level, sure, it’s easier to build a rocket than it is to reduce child poverty, but the policy decisions that underpin them are necessarily complex.

Even if a problem is complicated, implementing a solution to it is a complex task. Another way to frame this point is that we are always solving a complicated problem in a complex environment, where surrounding contexts, user needs and priorities are constantly shifting. A glaring example is history of the Choluteca Bridge in Honduras. The bridge was built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930s and was long considered to be one of the greatest works of architecture in the country. After Hurricane Mitch hit Central America in 1998 the Choluteca Bridge was still standing, but there was just one problem. The roads on either end of the bridge had completely vanished and river itself had changed its course. Though structurally flawless, without attention to shifting realities on the ground, the bridge was not able to serve its purpose.

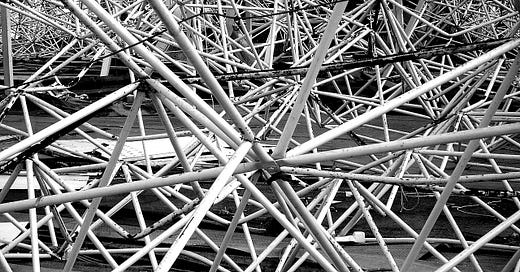

Scale matters. As I have previously written, the fundamental challenge of sense making is that our experience of the world cuts across multiple scales. When we attempt to codify a problem, though—using methods like systems mapping—we tend to make it complicated by mapping only those elements of the system that are visible at the same scale as the problem under examination. My colleague Ryan Young has a great example of this phenomenon: if you ask a group to create a system map of political and social dynamics in the Middle East, most attempts will miss the local and personal dynamics that lead to a young man in Tunisia setting himself alight and triggering the Arab Spring. Complicatedness relies on single-scale dynamics, which very seldom manifest in the real world.

A little less classification, a little more action

Now, obviously there are benefits to being able to distinguish different types of problems, even if it is difficult to classify them exactly. Classification helps to inform different whether different types of analysis or action are appropriate in particular contexts. But I’m really not sure whether a classification system that frames policy and public management problems as simple, complicated or complex makes us more effective at getting the kind of outcomes we ought to value. Instead, I wonder if we should spend more time asking questions like:

What kind of complexity am I dealing with here? (if all systems are complex systems, all problems will exhibit some form of complexity).

What does the kind of complexity I am encountering mean for the way I want to influence the system/achieve a given outcome?

Can I learn anything from previous experience attempting to influence similar dynamics in similar ways?

All situations are complex, but not to different degrees, they are qualitatively different types of complexity—some that might be easier to respond to, others not. That demands more situational awareness before acting, but a better framework probably isn't the answer.

By the way: This newsletter is hard to categorise and probably not for everyone—but if you know unconventional thinkers who might enjoy it, please share it with them.

Find me elsewhere on the web at www.lukecraven.com, on Twitter @LukeCraven, on LinkedIn here, or by email at <luke.k.craven@gmail.com>.

Hi Luke - I like your thinking ( and writing). I love the quote around simplicity on the other side of complexity ( Attributed to Oliver Wendell Holmes) and also love the idea of going through complexity to a more elegant simplicity. I agree that we should focus more on action - but action ( and policy) should have an elegant simplicity that takes into account the complexity of the issue.